The “Coding For” Fallacy

Why can’t clinicians be more specific?

The outcry echoes in the back offices of health centers: “Physicians pick the diagnoses and bill for their encounters - but they never do it correctly! Their diagnoses are obsolete, or not specific enough, or missing laterality, or need an add-on code… how is it they got through medical school, but can’t pick the right diabetes code? How hard could it be?”

The complaints and accusations are both well-founded and misguided. There is a real problem, but it has little to do with intelligence, training, or even willingness. And the problem has a solution. The key is all about functional EMR design.

Background

For the uninitiated, when clinicians “code”, they primarily do two things: pick a billing code for the service they provide (like a surgery, or a primary care visit), and pick a diagnosis code that justifies the charges (like appendicitis, or hypertension). It’s more complicated in practice, but that’s the general idea. This article deals specifically with the latter activity: coding for diagnoses.

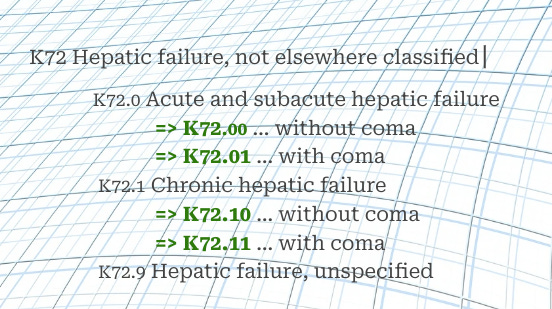

Diagnoses are primarily designated using the infamous “International Classification of Diseases” (ICD) coding hierarchy. The origins of the ICD scheme go back to the late 1800s, when it was developed for the purpose of tracking diseases. It has expanded immeasurably over the years, and the current version, ICD-10, contains tens of thousands of codes. Most correspond to medical symptoms and diagnoses; many are add-on codes for disease attributes; others designate patient status, health risks, events, or reasons for getting care.

Examples:

Disease code: E11.9, Type 2 Diabetes without complications

Add-on code: Z79.4, Long term (current) use of insulin

Patient status: Z66, Do not resuscitate

Health risk: Z80.4 Family history of ovarian cancer

Health event: W37.0XXA Explosion of bicycle tire, initial encounter

Reason for care: Z00.0 Encounter for general adult medical examination

In a traditional fee-for-service model, a primary care clinician submits charges for each office visit or procedure to a payer (insurance company, Medicare, etc.). They justify each charge with appropriate ICD-10 diagnostic codes. If the diagnosis codes - and other documentation - don’t support the service, the clinic can fail an audit, lose money or even be accused of insurance fraud.

The world of primary care is rapidly moving away from fee-for-service toward a value-based model of care. In this model, the provider is not paid for each visit or procedure; they are paid a predetermined, negotiated amount, often called a “capitation”, as a per-patient-per-month (PPPM) disbursement. The clinic agrees to do whatever it takes to provide primary care for the patients covered by that payer, and to accept the PPPM capitation in return. If they are efficient, they save money. If they’re not, they lose money. There is much more to value-based care in practice, and many variations, but that’s the general idea.

One would think that if visits are not individually billed, the ICD-10 diagnosis codes would be less important. But that is not actually the case. The capitation amount isn’t one-size-fits-all; it’s only fair that a clinic taking care of very complex and sick patients receives higher reimbursement than one caring for mostly healthier patients. For this reason, reimbursement is guided by a numeric index of complexity, or risk score, assigned to a provider organization (like a clinic). The higher the risk score, the higher the PPPM capitation. And one way the payer determines the risk score is through ICD-10 diagnosis codes passed to them by the billing clinicians, generally over the preceding year. So ironically, in a value-based care environment where reimbursement is no longer dependent on individual visits, billing those visits with the correct ICD-10 codes becomes more important than ever.

Risk scores are calculated by assigning an individual weight to each ICD-10 code or group of codes. The more complex and specific the code for a medical problem, the higher its weight. For example, E11.9, Type 2 Diabetes without complications has an assigned weight based on the predicted expenses for that disease, but E11.42, Type 2 diabetes with diabetic polyneuropathy is more specific and adds more to the total risk score. Similarly, N18.32 Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 3b carries more weight than N18.9 Chronic Kidney Disease, Unspecified. If the most specific codes are routinely used, it drives up the total risk score for the clinic, and the capitation increases.

So why is this such a challenge? The treating clinician is in a perfect position to characterize the diagnoses in question. They have to pick a diagnosis to document their work, so why not pick the right one? Why can’t they be better trained? How hard can it be?

Herein lies the fallacy, the misunderstanding that keeps clinical leadership, billing departments, and financial leadership in contention. This conflict has festered for years and grown deep roots. Billing directors lament the coding problem to CFOs, who complain to CEOs, who push back on CMOs (Chief Medical Officers). The chorus: “we need clinicians to code better!” This often results in the hiring of consultants to conduct billing and coding training for clinicians, at considerable cost. It results in hiring extra billing staff to correct mistakes and provide feedback. But these efforts generally have a modest effect on clinician behaviors, because the problem does not originate with the level of clinician training, knowledge, or willingness. It is a core problem with the clinical informatics of EMR design.

The root of the problem

When a clinician diagnoses a medical problem for the first time, they use a search engine within their EMR to pick an official, coded diagnosis. If it’s a new problem, they may not yet have all the details, so they may select a fairly generic version with a correspondingly nonspecific ICD-10 code. The clinician will also usually add the diagnosis to the patient's official, ongoing problem list. Clinicians and staff use the problem list constantly, as the fastest means of digesting a patient’s story at a glance; so if a diagnosis requires treatment, it is usually important enough to go on this list.

When the clinician treats the patient again for the same condition, they may know more. If it is chronic kidney disease, they may have the lab results to stage it more specifically. If it is heart failure, they may have echocardiogram results to differentiate the type of failure. This would be the perfect time to pick a more specific diagnosis. But the clinician often doesn’t search for a new problem at that point; they instead pick one from the existing problem list, such as the non-specific diagnosis from the previous visit. It looks like they are just taking the easy way out, but in fact clinicians have reasons that go far beyond convenience.

If the clinician looks up and uses a new, more specific diagnosis, things can get complicated. First off, the less specific problem name is easy to read, like I50.9 Congestive heart failure; the more specific diagnosis may have an elaborate name, like I50.43 Acute on chronic combined systolic (congestive) and diastolic (congestive) heart failure. Not only is it long, but the words “heart failure” are at the very end. And while problem descriptions vary between EMR systems, the more specific ones are always longer and more difficult. Patient problem lists in an EMR are generally displayed in a column, and these long names wrap awkwardly into two or three lines. Choosing problems in the “ideal” fashion can take the problem list from effective and digestible to jumbled and frustrating.

Adding the more specific code also results in two versions of the problem on the patient’s problem list; EMRs can add new problems, but don’t generally allow merging them. And when a clinician documents and treats under the new diagnosis, the history of treatment for that medical problem is now split in two. Someone reviewing the chart has to read the story in two places (under two diagnoses) to have the whole picture. And when the clinician “cleans up” the problem list by retiring the less specific diagnosis, the treatments and orders associated with it are essentially hidden in an “inactive” list; they are technically still available, but are unlikely to ever be seen in practice.

It doesn’t end there; prescription renewal requests from pharmacies want to match the original diagnosis under which they were prescribed; recurring orders from previous encounters will be associated with previous diagnoses; pulling forward appropriate documentation from a previous encounter, for accuracy and efficiency, becomes more complicated. The difficulties vary from one EMR to another, but are quite a snarl in pretty much every case.

And it gets even worse due to the insanity of ICD-10. Recent versions of ICD have evolved to be much more attuned to the needs of billing and other administrative purposes than to the needs of medical practice. For instance, for many diagnoses, there is one ICD-10 code for the first time a problem is treated, and another for the second time - even though it is the SAME MEDICAL PROBLEM! For instance, imagine the story of a severe wrist sprain, with complications, being scattered among these “diagnoses”:

S63.522A Sprain of radiocarpal joint of left wrist, initial encounter

S63.522D Sprain of radiocarpal joint of left wrist, subsequent encounter

S63.522S Sprain of radiocarpal joint of left wrist, sequela

It’s no wonder a primary care clinician is likely to simply pick M25.532, Pain in left wrist and document all three visits under that problem.

Coding for diabetes is a fiasco all its own. If a patient has multiple complications, ICD-10 represents them as separate “forms” of diabetes, like:

E11.42 Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic polyneuropathy

E11.3293 Type 2 diabetes mellitus with mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy

without macular edema, bilateral

Imagine a patient has both of these, and their primary care clinician increases their insulin to keep their sugar under control. Which problem do they use for their documentation and orders? Diabetes with neuropathy (nerve damage) or with retinopathy (eye damage)? It is anyone’s guess. They didn’t actually address either problem - or rather they addressed them both, by controlling the diabetes itself. The diabetes story gets scattered among any number of diagnoses over time.

To combat this, the clinician may keep undifferentiated Type 2 diabetes on the problem list, and use it every visit - not because they are lazy, but because a generalized, categorical problem list helps clinicians document and place orders in one clear place in the EMR, which preserves the patient’s timeline, makes the chart readable and facilitates better care. But when they do so, they are also attaching that non-specific, low-complexity diagnosis to the charges for that visit. So as far as the payer is concerned, the patient doesn’t have any complications from their diabetes! When this practice is widespread among clinicians it has a detrimental effect on the risk scores, and can lower the capitation for value-based reimbursement.

The solution

There is a better way. This problem is solvable. Not at the level of clinician behavior, but at the level of functional EMR design. It means changing the relationship between real-life medical diagnoses and the underlying code structures used for billing. It means adding new layers of abstraction, and creating dynamic associations and rules. It means allowing clinicians to maintain an organic, readable chart record, while facilitating detailed, accurate and specific billing. This approach is also ripe for the use of AI to improve its accuracy and ease of use.

In this follow-up article & video, I describe one potential EMR design to address this challenge: Functional EMR Design: Diagnosis Search and Select.

The Functional EMR Guy: This channel offers a view of ambulatory EMR technology from my experience as a clinician, clinical informaticist and software engineer. My driving vision is a practical approach to functional analysis and design, to help clinicians help patients by creating better EMR systems. Please subscribe! I won’t send spam or share your info.

Love it, James! Great diagnosis of an important and pervasive problem in health care. Liked this line in particular..."a generalized, categorical problem list...preserves the patient's timeline, makes the chart more readable, and facilitates better care."

Very clear description of a horrible problem