Obstacles to Innovation, Part 3

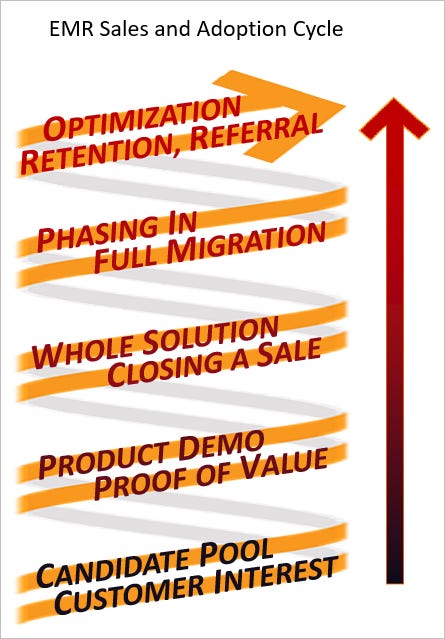

In part 1 of this article we concentrated on the early phases of the EMR adoption cycle and its effects on innovation, followed by a contrasting description of an idealized sales demo in part 2. We’ll conclude by going back to the EMR Adoption Cycle diagram to examine the remaining steps and how they affect innovation:

The Whole Solution, and Closing a Sale

The process of final product selection should involve many departments and stakeholders, lots of demos and thorough testing. But generally the process falls short for non-clinical stakeholders, like front desk, scheduling, clinical support, medical records and IS. A few of the reasons:

Without setting up things like departments, users and schedule templates, it is difficult to test operational and office functions. Customization only happens after purchase.

Lab interfaces, electronic prescribing, document processing and other places where the EMR meets the real world, cannot be set up or tested before product installation.

Claims and billing solutions can't be tested pre-sales, and are hard to test, period. And billing functionality differs dramatically between practices, payers and states, adding more unknowns.

Technical performance of a demo environment is a poor predictor of performance at go-live. When the demo system has performance problems, salespeople generally say, "that's because it's the demo system, the live system is better." And usually it is. But not always, and not in all ways. A live system may have specific performance issues that the demo system does not expose.

In short, the non-clinician stakeholders, like clinical stakeholders, seldom learn enough to feel confident with a selection. This is true even with widely used products.

But why do sales matter so much? A customer's experience after going live should be what drives the future of the market. But it doesn't really pan out that way.

Phasing In and Full Migration

The successful rollout of most software products depends on pilot projects, staging, testing and quality improvement cycles. Yet most health center organizations go live all at once, in "big-bang" fashion, with all aspects of the product at once - clinical, operational, billing, patient engagement - everything. A large health system that runs many separate hospitals and clinics can execute this approach one hospital or health center at a time, and learn as they go. But an independent entity, like a Community Health Center, doesn’t have that luxury.

I described this recently to a friend of mine, an engineer and expert agile coach, and he couldn't get his head around it - effectively he didn't believe me! And this speaks to how different the EMR space is from software for other industries. The factors that push customers toward a big-bang approach are numerous; here are a few:

Virtually all customers are migrating to a new system from an existing EMR, so a phased approach would mean keeping parallel systems in operation.

The major functional parts of a product, like clinical and financial modules, are usually inseparable. Phasing in one functional area at a time requires separation and integration that just isn’t there.

Patient data must be complete at every juncture, especially in primary care. If a user enters patient data in a new system, that patient's record in the old system is immediately incomplete. And the two EMRs have incompatible databases, so there is no automated mirroring of entered data, ever.

The financial connections are impossible to phase in. Claims can stretch out over months. Bank accounts are linked to products in proprietary ways. Much more, most of which is over my head.

The outside connections for prescribing, ordering, receiving results, communicating with patients, etc. generally can't talk to two EMRs at once, due to proprietary technology, and many other reasons.

This is an incomplete list, but hopefully gives an idea of the challenges. One might ask at this point whether making a product easier to migrate to (and migrate from) might not be an incentive for innovation. But customer retention in the EMR space doesn’t work that way.

Retention and Referral

Customer retention in the EMR market is also unique. Once a health center goes live with a product, no matter how it goes, they are loath to go through the process of change again. Full migration to a new system is often described as traumatic for everyone involved. Productivity suffers for weeks to months. Reestablishment of optimal workflows takes from six months to two years - the larger and more complex the health center, the longer. If existing patient data is migrated between systems, the effort is mammoth and error-prone. If only minimal data is migrated, clinicians must use an archive solution to see older content - which means looking in two places to see a reasonably complete patient history for years.

Users will put up with tremendous inconveniences, create elaborate workarounds, and become wed to them, rather than consider the workflow restructuring and retraining involved in a migration. Even if a clinic realizes a new EMR was a mistake, it is seldom used as a reason to make the next transition. In fact, it can be the opposite:

“Remember how hard our last migration was? Let’s figure out how to make this product work. How do we know another product is better? We might make the same mistakes. Anyway, if we announced another product change right now, many employees would quit.”

After a while, users start to defend their EMR selection, regardless of product faults. They have often put their hearts and souls into the optimization and maintenance of a system, for months or years, and are proud of their work. When users talk with their colleagues at other organizations, they often come away feeling that their experience, while difficult, is par for the course.

For many years I have been asking clinicians, off the record, what they think of their EMRs. Virtually all the truly enthusiastic users I have met are “EMR champions” for their organizations. Ordinary users, at best, say things like "it's not bad, we get by", or "it's improved a lot over the years, you get from an EMR what you put into it." At worst, the EMR is immediately cited as the hardest part of a clinician's work life. Granted, users sometimes lump unrelated difficulties in their practice under the heading of “EMR”, but the point still stands.

There is a gradual, insidious phenomenon at work that goes beyond the software. Clinicians have been slowly drained of their autonomy, their time and their energy. They have been drained not just by EMRs, but by quality programs, credentialing organizations, liability concerns, productivity requirements, insurance companies and government regulations. All these entities want a piece of the clinicians' time, a slice of their attention, a change in their practice, and a few extra clicks of their mouse, over and over, all day long. It is chronically exhausting. We're tired of complying, but just as tired of complaining. We've heard "no" so many times, in so many ways, that we stop asking questions. And when users become apathetic, they no longer communicate what they really want and need, and they themselves become poor drivers of innovation.

And still, I believe all of this can be gradually overcome. But it will take a new approach.

The Functional EMR Guy: This channel offers a view of ambulatory EMR technology from my experience as a clinician, clinical informaticist and software engineer. My driving vision is a practical approach to functional analysis and design, to help clinicians help patients by creating better EMR systems. Please subscribe! I won’t send spam or share your info.

This is incredible, thank you James!

Enjoyed your post, thank you

I retired from an office Ortho practice some 7 years ago.

As a first time adopter of an emr in a small ortho office practice (just one assistant/secretary we made progress and made the product work for us. But, I must admit, we limited the use of the tech to the minimum and kept our records lean.

The experience you describe for many is daunting and I concur completely with the feeling that ones individuality and needs was being stifled or left unmet. For me, the lack of easily accessed imaging was a huge frustration, eased I think in recent years